The Art of Pulp Horror is a beautiful book, collecting the art of horror and contextualizing it with a series of essays. It’s also an important book, demonstrating that as editor extraordinaire Stephen Jones puts it, “Whereas the public has always been eager to consume gratuitous and gory tales as a form of escapist entertainment, there have always been those who believed themselves to be morally superior to the masses and have done their best to curtail or ban such things.”

The most resonant effect of those trying to block horror, which has happened again and again with the Motion Picture Production Code, the Comics Code Authority, and the British NVALA, is a lack of respect for the genre. It’s something obvious in award shows (Toni Collette really did deserve at least a nomination for her performance in Hereditary) and mainstream reception of horror media. It has tangible effects as well: lost films, magazines, and comics. Essayist Richard Harland Smith writes that at one point, Robert “Florey [who was originally slated to direct Frankenstein] shot a (now presumed lost) 20-minute test for his vision of Frankenstein… [starring] a reportedly grumpy Bela Lugosi as the Monster.” It’s tantalizing footage that might still exist today if horror wasn’t constantly denigrated.

RELATED: Parasite’s Big Night at the Oscars is a Big Win for Horror

Harland Smith is one of nine writers (not counting Jones or the foreword by pulp legend Robert Silverberg) who penned a chapter. His segment of the book focuses on “Pre-Code Horrors,” which fits his expertise as a film historian. The other segments, starting with the “Penny Dreadfuls”of the nineteenth century and stretching to the “Boom and Bust” of twentieth century paperbacks, are written by experts in those respective fields. So book experts write about books, comic experts about comics, film experts and films. It certainly leads to a higher quality for each individual chapter.

The downside is that there is rarely interplay between the topics. Lisa Morton, who contributed “Drive-In Delinquents” likely hadn’t read Gregory William Mank’s “Poverty Row” or Barry Forshaw’s “Seduction of the Innocent” before writing her own chapter. While Jones does good work making sure that there isn’t unnecessary overlap, there also isn’t reflection on how the pulps influenced Universal Horror. Each section is cordoned off.

The most glaring omission is a lack of commentary on racist tropes. There are pages and pages of art from the notoriously racist Fu-Manchu series, which featured white actors playing Asian characters and inflamed anti-Asian sentiment. The art should absolutely be included, as should H.P. Lovecraft’s covers. These pieces may be problematic, but they’re a part of the genre’s history. To include them in the book without addressing their bigotry feels like tacit agreement though.

Those sections are small, and don’t outweigh the book’s positive qualities. The Art of Pulp Horror is a great overview of the genre’s history in the U.S., unrestricted by medium. Most books of this type focus on one era — Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks from Hell goes deep into the horror books of the 60s-80s — and one medium — David J. Skal’s The Monster Show does a thorough job with the intertwining biographies of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff for example. None of them offer as comprehensive a history as The Art of Pulp Horror.

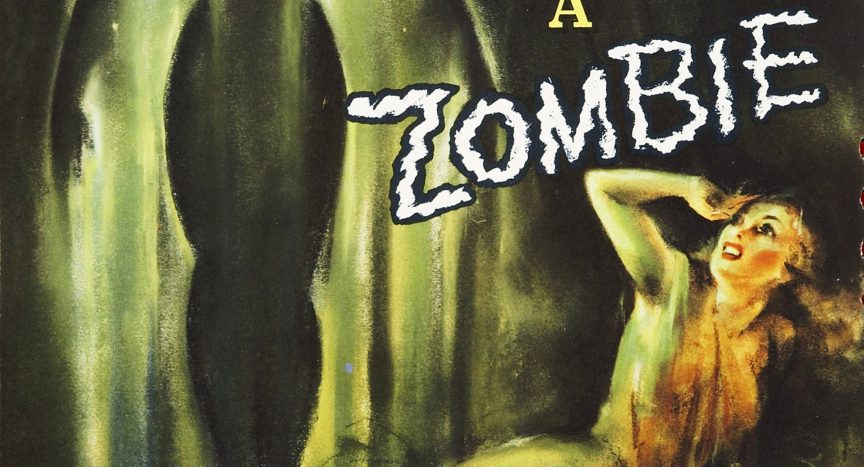

The artwork inside is gorgeously printed. There’s no stronger argument in the book (or outside it) than looking at the pictures themselves. They’re lurid, bloody, and were oftentimes created as fast as possible, but more than anything else they’re a lot of fun to look at. The world would be a better place if doctor’s offices would replace those months old golf magazines and Sports Illustrateds with The Art of Pulp Horror.

Wicked Rating – 8/10

The Art of Pulp Horror was published by Applause Books August 15, 2020.