Horror is evolving as a genre. Although your local multiplex is still peppered with the usual contenders, look a bit closer at the schedule and you’ll find the latest drama, thriller, or crime offering is closer to horror than you might expect. In this bi-weekly series, Joey Keogh presents a film not generally classified as horror and argues why it exhibits the qualities of a great flight flick, and therefore deserves the attention of fans as an example of Not Quite Horror. This week, it’s David Fincher’s luscious, brooding adaptation of Gone Girl.

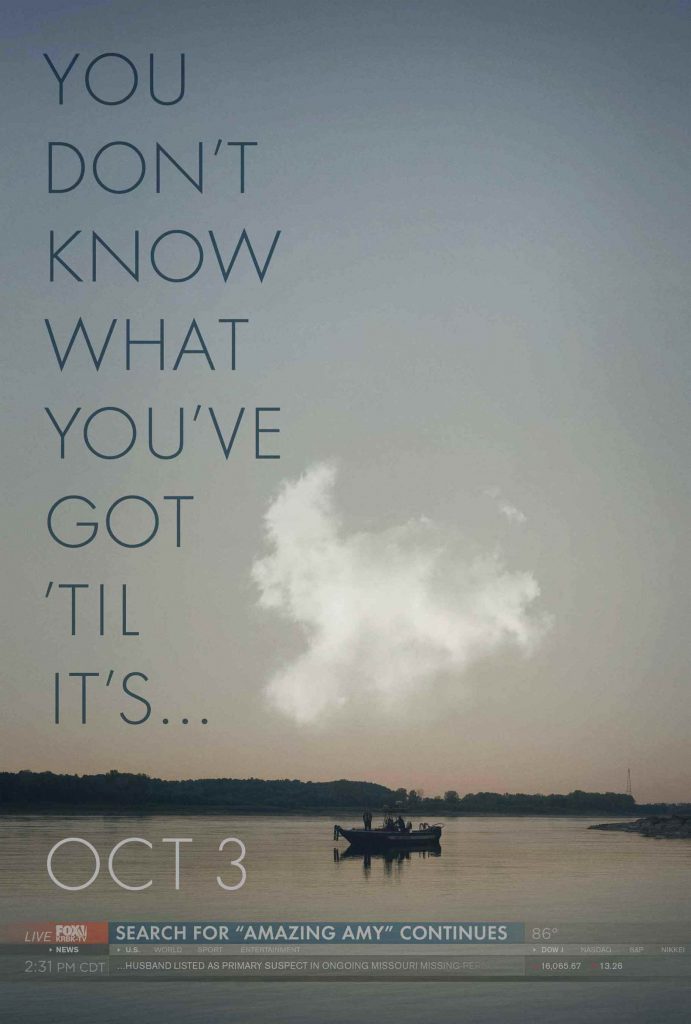

David Fincher is fast becoming the unofficial master of Not Quite Horror, with Zodiac, 2011’s The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo remake and now Gone Girl. Fincher’s gloriously vicious adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s popular mystery thriller was more widely anticipated than Fifty Shades Of Grey, and considering how even celebrities braved the multiplexes to flock in their droves to see it, its impact cannot be understated. More importantly, though, Gone Girl is a triumph, not just of Fincher’s innate and incomparable ability as a director, but as an example of just how well he can freak us out without actually doing anything too outwardly scary.

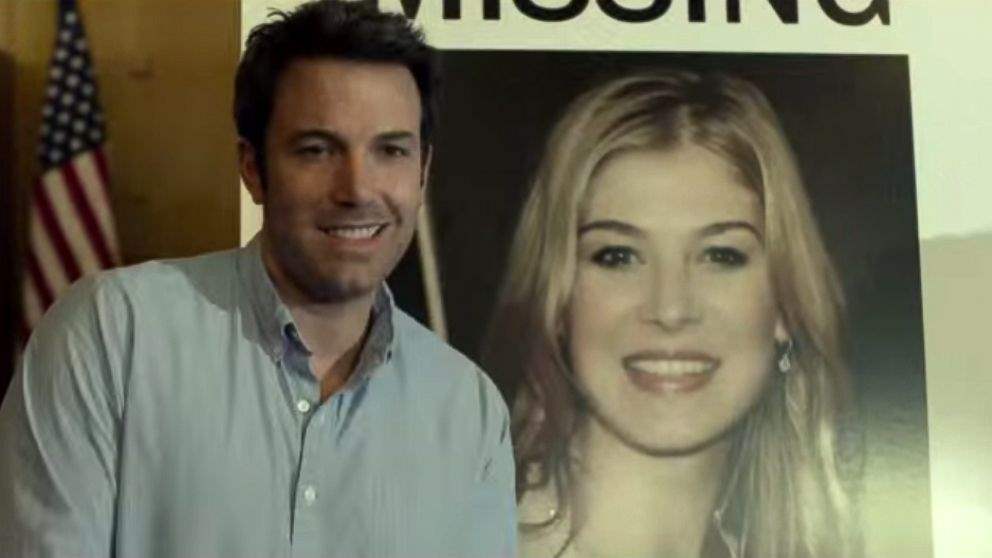

Save for an unforgettable burst of gory violence towards the end (more on that later), Gone Girl is a largely bloodless affair. The tension comes from the hive of activity surrounding alleged wife-murderer Nick Dunne, a closed-off, borderline emotionless hunk of machismo played with incredible restraint by Ben Affleck. Long underrated as a performer, Affleck shines in a role that requires him to both utilise his good looks and charm, and satirise them (early on, he’s told his chin makes him seem untrustworthy-something that is true of both men). The idea that Nick may have killed his wife is the hook on which the entire first act of the film hangs, setting up a conceit that the second half then carefully unravels, and it’s testament to both Affleck and Fincher that it’s never quite clear whether Nick is innocent or not.

The very first shot of Nick, looking totally fed up as he takes the garbage out in front of his McMansion, is telling but not as much as that of his wife, the scheming, psychotic Amy, to whom his inner monologue poses the rhetorical question; “What have we done to each other?” Amy and Nick are complex, fascinating characters and their weird, dual narrative (jumping from her perspective to his, and back to their happier days together) is so slow to reveal its true secrets that it’s painfully tense at times–especially after a particularly explosive, midway revelation. Although Gone Girl seems at first to be Nick’s story, it’s really Amy’s and with her Fincher has found a villain who could easily stand toe-to-toe with the likes of Se7en‘s John Doe for manipulation, and the ease with which useless people are disposed.

Amy’s madness is hinted at in the beginning, but the real revelations come in bursts–shocks of creativity that are so clever and devious, it’s hard not to be impressed by her. The biggest shock comes in the murder of her once-paramour, the gormless Desi (played here by Neil Patrick Harris, in a bit of annoying stunt casting), mid-coitus. After slashing his throat with a box-cutter and being covered in gushes of blood, Amy takes a single breath and flips her hair back out of her face. It’s a stunning moment that captures her insanity and ingenuity, followed up by a highly-rehearsed interview in the hospital during which “she confesses” to being raped (naturally, she fakes her injures with a wine bottle).

Amy’s madness is hinted at in the beginning, but the real revelations come in bursts–shocks of creativity that are so clever and devious, it’s hard not to be impressed by her. The biggest shock comes in the murder of her once-paramour, the gormless Desi (played here by Neil Patrick Harris, in a bit of annoying stunt casting), mid-coitus. After slashing his throat with a box-cutter and being covered in gushes of blood, Amy takes a single breath and flips her hair back out of her face. It’s a stunning moment that captures her insanity and ingenuity, followed up by a highly-rehearsed interview in the hospital during which “she confesses” to being raped (naturally, she fakes her injures with a wine bottle).

Rightly nominated for an Oscar for her performance, English actress Rosamund Pike finds her meatiest role to date in Amy. Mostly known for much lighter fare (in fact, she had a family comedy out in UK theatres around the same time as Gone Girl), Pike was an odd choice for Amy, but she immediately silenced her critics with a brave, warts-and-all performance from which the majority of female actors would shy away. And, in a rare example of the film improving upon the novel, Fincher’s Gone Girl gives Amy and her long-suffering husband a more realistic ending. She still gets away with it, but he manages one final (literal) blow before succumbing to spending the rest of his life with her.

This particular moment of violence was one of the main talking points about the flick, and was seen by many as a step too far. Given how ridiculously PC the world is nowadays, it was only natural that certain commentators would be up in arms about a man shoving a woman into a wall and calling her the c-word – even a woman who tried to frame her husband and get him sentenced to death. But this moment had to happen, and it fit perfectly within the narrative. It’s the one moment Nick lashes out, the one time his stone exterior crumbles, after being held together for so long. The saddest part about it is that, although he had been pushed to his breaking point several times over, after deciding to come clean on national TV he finds that Amy has bested him again. And this time it’s probably for life.

Much like The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, a haunting score by Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor (Rolling Stone described it as “sublimely uneasy”, which is a fitting description for the film itself, too) contributes to and, at certain moments, creates Gone Girl‘s brooding atmosphere. The first strums establish that something is a bit off, even though they’re outwardly light-footed–we know something’s wrong but we can’t quite figure out what. As more and more secrets are revealed, the score cleverly switches tempo depending on what’s happening, sometimes treading lightly (as in the flashback sequences), and often bordering on Nine Inch Nails levels of machine-like grumbling (when everything starts falling apart). It’s the perfect accompaniment to the dark fantasy playing out onscreen, because it never lets up, even in the movie’s quietest moments. The nastiness of Fincher’s take on Gone Girl isn’t confined to how Amy tears people apart, the film is also an unnervingly realistic look at marriage, the media’s obsession with tragedy and how quick we, as a society, are to judge the supposedly guilty. Key peripheral characters like Patrick’s Fugit’s young cop, who openly hates Nick and considers him guilty from the outset, and Missy Pyle’s obnoxious talk show host, who brands him a sociopath with no real proof other than a photograph, represent the different, often quite vocal, factions who emerge when something terrible happens. As hotshot lawyer Tanner Bolt, who’s seen it all before and worse, Tyler Perry gets some of the best, and most telling, lines of the movie, quipping to Nick, after explaining he has no option but to succumb to life with his wife; “Just don’t piss her off”.

The nastiness of Fincher’s take on Gone Girl isn’t confined to how Amy tears people apart, the film is also an unnervingly realistic look at marriage, the media’s obsession with tragedy and how quick we, as a society, are to judge the supposedly guilty. Key peripheral characters like Patrick’s Fugit’s young cop, who openly hates Nick and considers him guilty from the outset, and Missy Pyle’s obnoxious talk show host, who brands him a sociopath with no real proof other than a photograph, represent the different, often quite vocal, factions who emerge when something terrible happens. As hotshot lawyer Tanner Bolt, who’s seen it all before and worse, Tyler Perry gets some of the best, and most telling, lines of the movie, quipping to Nick, after explaining he has no option but to succumb to life with his wife; “Just don’t piss her off”.

It’s a throwaway moment that exemplifies the strength of the movie, because we are complicit in Amy’s deceit. Gone Girl is a film that is predicated on our willingness, as an audience, to assume somebody’s guilt and it can often be a voyeuristic experience. Although it’s obvious that Amy is in the wrong, it’s hard not to root for her to succeed. And, even though Nick doesn’t necessarily deserve what’s happening to him, he’s been complacent and he’s strangely implicit also. Cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, who also lensed The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, bathes his palette in light blues, golds and greys, capturing the desolate landscape of small-town Missouri and highlighting how isolated Nick is from the real world.

This is a very careful film. It’s clear Fincher has given great thought, as he always does, to how each moment will be received by the audience. Exchanges are often delivered in hushed tones, so we must strain to hear what’s going on, and underneath everything the Ross/Reznor score seeps into our consciousness to plant seeds of inescapable doubt. Much like Nightcrawler, the villain/anti-hero of the piece remains unpunished, rooting the movie in real life where, more often than not, good doesn’t triumph over evil. In fact, the true horror of Gone Girl is its honesty, from Amy’s success to Nick’s unwillingness to leave her. But what’s ultimately most terrifying about it is how easily we begin to believe in Nick’s guilt, and how often our supposedly deeply-held beliefs are called into question. In the end, if we were in the same situation as he is, could we honestly pretend we would behave any differently?