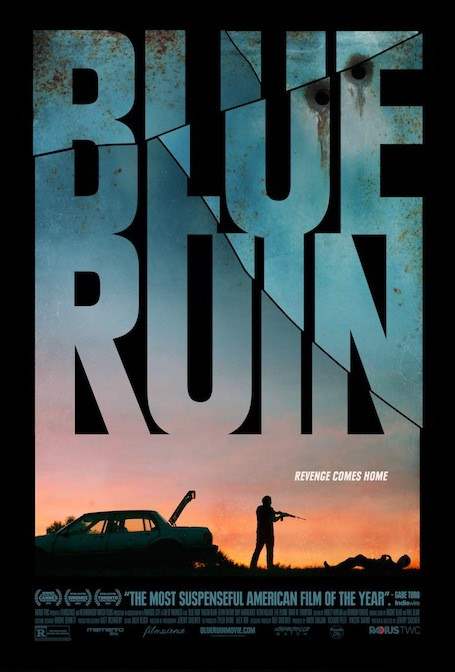

Horror is evolving as a genre. Although your local multiplex is still peppered with the usual contenders, look a bit closer at the schedule and you’ll find the latest drama, thriller, or crime offering is closer to horror than you might expect. In this bi-weekly series, Joey Keogh presents a film not generally classified as horror and argues why it exhibits the qualities of a great flight flick, and therefore deserves the attention of fans as an example of Not Quite Horror. This week, it’s the terrific Blue Ruin.

Films as special as Blue Ruin don’t come along very often and, when they do, they typically struggle to find the audience they deserve. Although it made waves on the festival circuit back in 2013, Jeremy Saulnier’s sophomore feature–starring his old high school buddy Macon Blair as a depressed man out for vengeance against his parents’ killer–only received a limited release both in the States and across the pond. Critics raved about it, and those who did manage to catch it passed the word along but, even so, this terrific little movie sneaked under most people’s radar.

This may be down to the fact that it, much like the similarly-themed Cold In July, which was released around the same time, was a hard sell to the mainstream market. Blue Ruin is basically a horror movie. It may not seem like it, at first, but it is. It’s not a drama, a thriller or, as IMDb is keen to describe flicks that are a little bit difficult to categorise, “crime”. This is the heartbreaking, horrifying, warts-and-all story of a desperate man with nothing left to live for, who commits a terrible crime in a misguided attempt to right a previous wrong and pays the price for it with his own life.

Writer-director Saulnier doesn’t pull any punches, ensuring we know from the start that Blair’s anti-hero Dwight is doomed. This is a man so broken that when he’s first introduced to us, he’s stealing a bath in the home of a family who are currently away on vacation. In direct contrast to Nightcrawler‘s Lou Bloom, who is established from the film’s opening moments as someone destined to succeed no matter what, it’s clear from the outset that whatever decisions Dwight makes will be the wrong ones. A broken, stumbling, meek little thing, his sudden bursts of anger towards those who destroyed his family are directly juxtaposed with everything else he does.

Writer-director Saulnier doesn’t pull any punches, ensuring we know from the start that Blair’s anti-hero Dwight is doomed. This is a man so broken that when he’s first introduced to us, he’s stealing a bath in the home of a family who are currently away on vacation. In direct contrast to Nightcrawler‘s Lou Bloom, who is established from the film’s opening moments as someone destined to succeed no matter what, it’s clear from the outset that whatever decisions Dwight makes will be the wrong ones. A broken, stumbling, meek little thing, his sudden bursts of anger towards those who destroyed his family are directly juxtaposed with everything else he does.

Living in his car (ostensibly by choice), he scrounges for food in dumpsters, while a local cop blatantly pities him. When he eventually catches up with his sister, he tells her he simply “isn’t used to talking this much”. Dialogue is sparse here, in general, with “he hurt my parents” being about as expository as Saulnier’s accomplished script gets. Blair, remarkable in his first leading role, communicates a myriad of feelings, particularly through his gentle, pained eyes. His expression as he watches his parents’ killer being released from prison is palpable and heartbreaking. Likewise, later, as he watches the man bleed out, his gaze is unwavering, his resolve strengthening with his dying gasps.

Although it seems, at first, that the alleged killer’s release is the beginning of Dwight’s downward spiral–as it sees him immediately spring into action, like a bear being awoken from hibernation–the murder is the real catalyst of Blue Ruin, setting a sequence of jarringly violent events into action that he soon learns cannot be undone. The real black heart of the film, and indeed the basis for its horror credentials, is slowly revealed as he finds himself at the mercy of his victim’s twisted, criminal family who, although horrid, are dealing with a loss just as he is. Dwight therefore becomes both the hero and the villain of the piece.

The central themes of revenge, respect, justice and family loyalty are explored without the usual Hollywood sheen to which we’ve become accustomed. Although Saulnier captures his native Virginia in gorgeously vast, sweeping shots, Blue Ruin is an otherwise un-showy film. Quiet and brooding, its sequences bleed perfectly into each other, with Blair often the only character onscreen for long stretches of time. Dwight is the exact opposite of the typical protagonist in such fare; scrawny, sloppy and reactive, as opposed to proactive. And, unlike the majority of revenge-seekers, he’s totally aware of his own mortality, even settling down to a last supper before the final confrontation and leaving a voice-mail for his enemies to ensure they know he’s waiting for them.

The central themes of revenge, respect, justice and family loyalty are explored without the usual Hollywood sheen to which we’ve become accustomed. Although Saulnier captures his native Virginia in gorgeously vast, sweeping shots, Blue Ruin is an otherwise un-showy film. Quiet and brooding, its sequences bleed perfectly into each other, with Blair often the only character onscreen for long stretches of time. Dwight is the exact opposite of the typical protagonist in such fare; scrawny, sloppy and reactive, as opposed to proactive. And, unlike the majority of revenge-seekers, he’s totally aware of his own mortality, even settling down to a last supper before the final confrontation and leaving a voice-mail for his enemies to ensure they know he’s waiting for them.

It’s this message that is emblematic of the crushing brilliance of Blue Ruin. Dwight notes, in a sad, monotone voice, that murder breeds murder, and revenge breeds revenge while his enemies listen in shock and disgust. Given this is a film composed of brutal, beautiful and often starkly opposed, images–Dwight pissing on the grave of his parents’ killer before carefully burying a member of their family–it’s this sequence, along with the soon-to-be iconic shot of Dwight in a bloodied white shirt, that hits home hardest. The family aren’t nice people, but watching them gather around to listen to the words of the man who’s out to kill all of them is still heart-breaking.

Blue Ruin is a bravely realistic and quite harrowing film, to its credit. However, there are some wonderful moments of black comedy, punctuated with violence – including when Dwight tries to remove an arrow from his leg, DIY-style, with tools from the local store and eventually passes out in A&E, or when he drives around with a man screaming in his trunk the entire time, only to ask “which one are you again?” when he eventually sets him free–break up what could’ve been a depressingly dark slog. Saulnier isn’t out to glamourise revenge, or encourage us to root for Dwight, but rather to show the damaging effects of holding grudges and seeking to correct a supposed karmic debt.

The murder itself (early on, instead of teased throughout) further drives home the point that violence begets violence. Dwight huddles in a bathroom stall, knife poised in a shaking hand, before lunging at his parents’ killer just as he’s finished washing his hands, ensuring he’s unable to react properly. He stabs him sloppily, haphazardly, in the neck and head, blood gushing everywhere, with no regard for the mess he’s making or the clues he’s leaving behind. There is no doubting that this isn’t the end of Dwight’s troubles but the beginning. And, in a film loaded with bone-crunching gore, the horror of the murder isn’t alleviated by the humour of its perpetrator’s ineptitude, it stews in it.

The murder itself (early on, instead of teased throughout) further drives home the point that violence begets violence. Dwight huddles in a bathroom stall, knife poised in a shaking hand, before lunging at his parents’ killer just as he’s finished washing his hands, ensuring he’s unable to react properly. He stabs him sloppily, haphazardly, in the neck and head, blood gushing everywhere, with no regard for the mess he’s making or the clues he’s leaving behind. There is no doubting that this isn’t the end of Dwight’s troubles but the beginning. And, in a film loaded with bone-crunching gore, the horror of the murder isn’t alleviated by the humour of its perpetrator’s ineptitude, it stews in it.

Blue Ruin is an incredibly affecting, disarmingly poignant revenge film with much to say about the nature of karmic retribution. Where most others of its kind would revel in the harshness of expletives or screamed accusations, Saulnier ensures we need to strain to hear what his protagonist is saying. Likewise, where most filmmakers would choose to leave Dwight storming off in a blaze of glory, Saulnier ensures he pays for his mistakes. The ending, in particular, could’ve easily played up its genre leanings, but instead it is harsh, cementing the story in the bitterness of reality.

Films like this don’t come around very often, and when they do, they ought to be celebrated for forcing us to reassess the conventions we so often rely on. Blue Ruin takes everything we think we know about revenge cinema and turns it on its head. Unflinchingly violent, harshly realistic, blackly comic and sporting an anti-hero so inept he can’t even shoot his victim from two feet away (and who has to puke en route to his big final act), it’s a triumph of Not Quite Horror. Catch it immediately, if not sooner.