Today is the release of The Scarlet Gospels, something that should excite most horror fans. This is it. This is the final Hellraiser story and it has been delivered full circle by original creator Clive Barker. I urge anyone with so much as a casual interest in the series to read the book. This is Clive Barker’s guide to Hell, the full, immersive Hell that exists outside the glimpses we saw in the films. Even the expansive labyrinth in Hellbound was not much more than a glorified hedge maze. The Scarlet Gospels is not necessarily Pinhead’s story, but he has an integral part to play in it. Pinhead’s journey is parallel to that of the novel’s protagonist, Harry D’Amour. D’Amour is a private detective who has appeared in numerous works from the author, a man who specializes in the occult and has spent his entire life searching for Hell. He’s always harbored a self-destructive desire to come face to face with the Devil, if only to say he did. The book takes him to Hell and back. Harry comes out the other side a changed man, having found a sense of purpose he was not necessarily looking for.

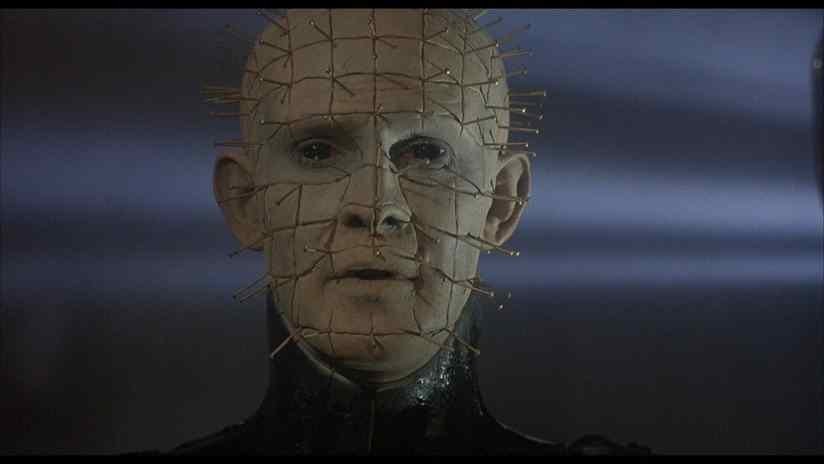

Pinhead, meanwhile, is searching for purpose. He drives the plot forward in a search for meaning, for a sense that all he has done has not been for nothing, and it is a search so destructive it threatens to tear apart the very fabric of Hell. This is a very changed man than the one we first glimpsed in Hellraiser. And this is not the androgynous Pinhead of The Hellbound Heart, either. But we saw the Hell Priest for a total of six minutes in the original film, how much could we really have gotten to know him in that time?

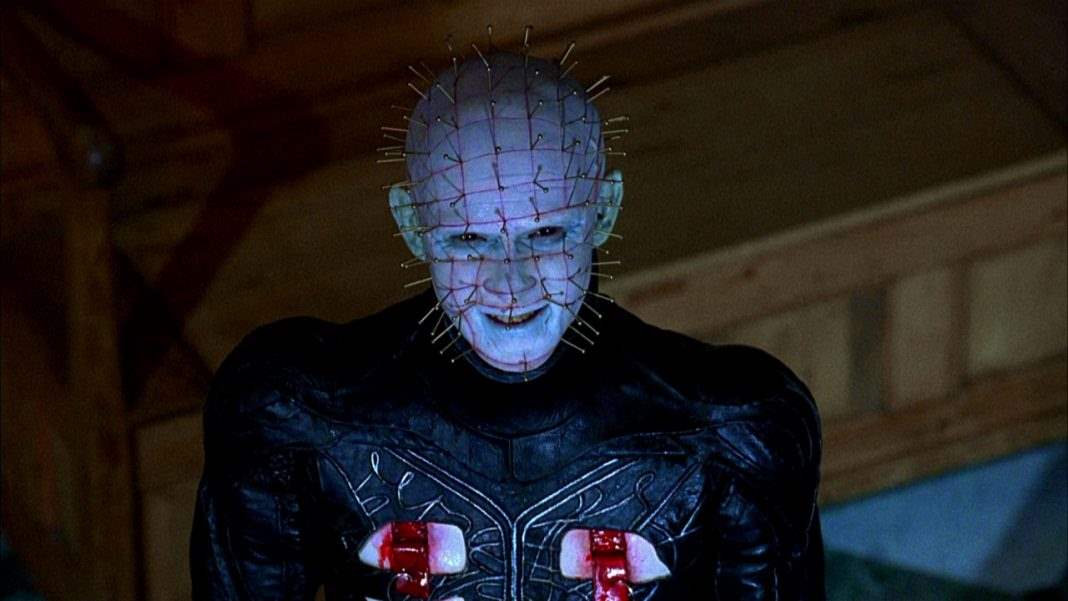

The book does not take readers too far into Pinhead’s past, which is good because it means it does not necessarily contradict the origin he was given in Hellbound: Hellraiser II. But it does go much deeper into his character, exploring the pierced cranium. He is at once more and less complex than readers thought he would be. His ambitions rank up there with traditional super villains, but they are the ambitions of a being at the end of his rope. A Priest who has devoted his life to a faith he no longer believes in. Pinhead has no shortage of arrogance in the book, more than we have ever seen, but it is all there to mask his doubt. And, yes, even his fear. When it is focused on the Cenobite, this is very much a chronicle of his final days. The Priest seems to be at least dimly aware of that, even as the plot first begins to set itself in motion.

The book does not take readers too far into Pinhead’s past, which is good because it means it does not necessarily contradict the origin he was given in Hellbound: Hellraiser II. But it does go much deeper into his character, exploring the pierced cranium. He is at once more and less complex than readers thought he would be. His ambitions rank up there with traditional super villains, but they are the ambitions of a being at the end of his rope. A Priest who has devoted his life to a faith he no longer believes in. Pinhead has no shortage of arrogance in the book, more than we have ever seen, but it is all there to mask his doubt. And, yes, even his fear. When it is focused on the Cenobite, this is very much a chronicle of his final days. The Priest seems to be at least dimly aware of that, even as the plot first begins to set itself in motion.

Barker first began talking up The Scarlet Gospels in the early 1990’s, around the release of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth. At that time, it was going to be a collection of stories similar to The Books of Blood, except that it would feature horrific and erotic stories in equal dosage. The collection was going to include a piece that pitted the Hell Priest Pinhead against Harry D’Amour. From that initial concept, it bloomed from a short into a novella and finally into the novel that sees release today. The one constant thing throughout all of that has been the promise that it would mark the death of the man with the pins in his head.

Rest assured, it does. He is not quite the Cenobite you know from the films and yet it’s impossible to see anyone but Doug Bradley bringing this character to life. The Pinhead you know from the early movies is in there, a part of him to be sure, but he is so far removed from the life he has led up until this point that he almost becomes a new character, a new man. While we meet him in the original movie as a being who would almost seem to wish death on himself, here he goes out like a rabid animal, lashing out wildly.

Rest assured, it does. He is not quite the Cenobite you know from the films and yet it’s impossible to see anyone but Doug Bradley bringing this character to life. The Pinhead you know from the early movies is in there, a part of him to be sure, but he is so far removed from the life he has led up until this point that he almost becomes a new character, a new man. While we meet him in the original movie as a being who would almost seem to wish death on himself, here he goes out like a rabid animal, lashing out wildly.

None of this necessarily contradicts his character. That sense of regality is still there. If anything, Pinhead’s journey is about rejecting everything about himself—he hates, for example, the nickname Pinhead—only to finally come to terms with exactly who he is. His ending is perfectly suited to his character, but of course that’s all I’m going to say about it.

Instead, let’s talk about the death of Pinhead. About the fact that one of the so-called second wave of famous monsters has shuffled off this mortal coil, finally coming to terms with his morality in the process. No other major movie monster has gotten that. Yes, there have been false final Fridays and Nightmares, but none of them have gotten the complete ending that Pinhead has been granted here, a proper sendoff by their own creator.

Even if there are Hellraiser films after this—and let’s face it, there will be—they can’t change the fact that the book exists. Pinhead is dead. Clive Barker promised that this would be the farewell to the Hell portion of his life forever and, boy, did he deliver on that promise. Everyone wanted one more work of horror from Barker, who turned to fantasy and YA fiction over twenty years ago, now they have it and it’s pretty clear that this is the last. It’s not just the final Hellraiser story, it’s the final work of horror from Clive Barker.

The reason each of the major 1980’s monsters persist to this day is the fact that they all seemed perfectly timed to either complement or contradict what had come previously. Jason Voorhees cemented himself as a box office icon pretty quickly. Audiences seemed to love this masked man, barely even a presence in those early features and even cheered for him. Michael Myers and Jason proved the value of the silent monster. Then, right as Jason promised his Final Chapter, Freddy Krueger emerged onto the screen. Krueger, obviously, was anything but silent. This was a monster that not only killed people, but invaded them. He intruded on their dreams and their most private fears. He was obnoxious, crude, saying anything to unnerve his prey.

The reason each of the major 1980’s monsters persist to this day is the fact that they all seemed perfectly timed to either complement or contradict what had come previously. Jason Voorhees cemented himself as a box office icon pretty quickly. Audiences seemed to love this masked man, barely even a presence in those early features and even cheered for him. Michael Myers and Jason proved the value of the silent monster. Then, right as Jason promised his Final Chapter, Freddy Krueger emerged onto the screen. Krueger, obviously, was anything but silent. This was a monster that not only killed people, but invaded them. He intruded on their dreams and their most private fears. He was obnoxious, crude, saying anything to unnerve his prey.

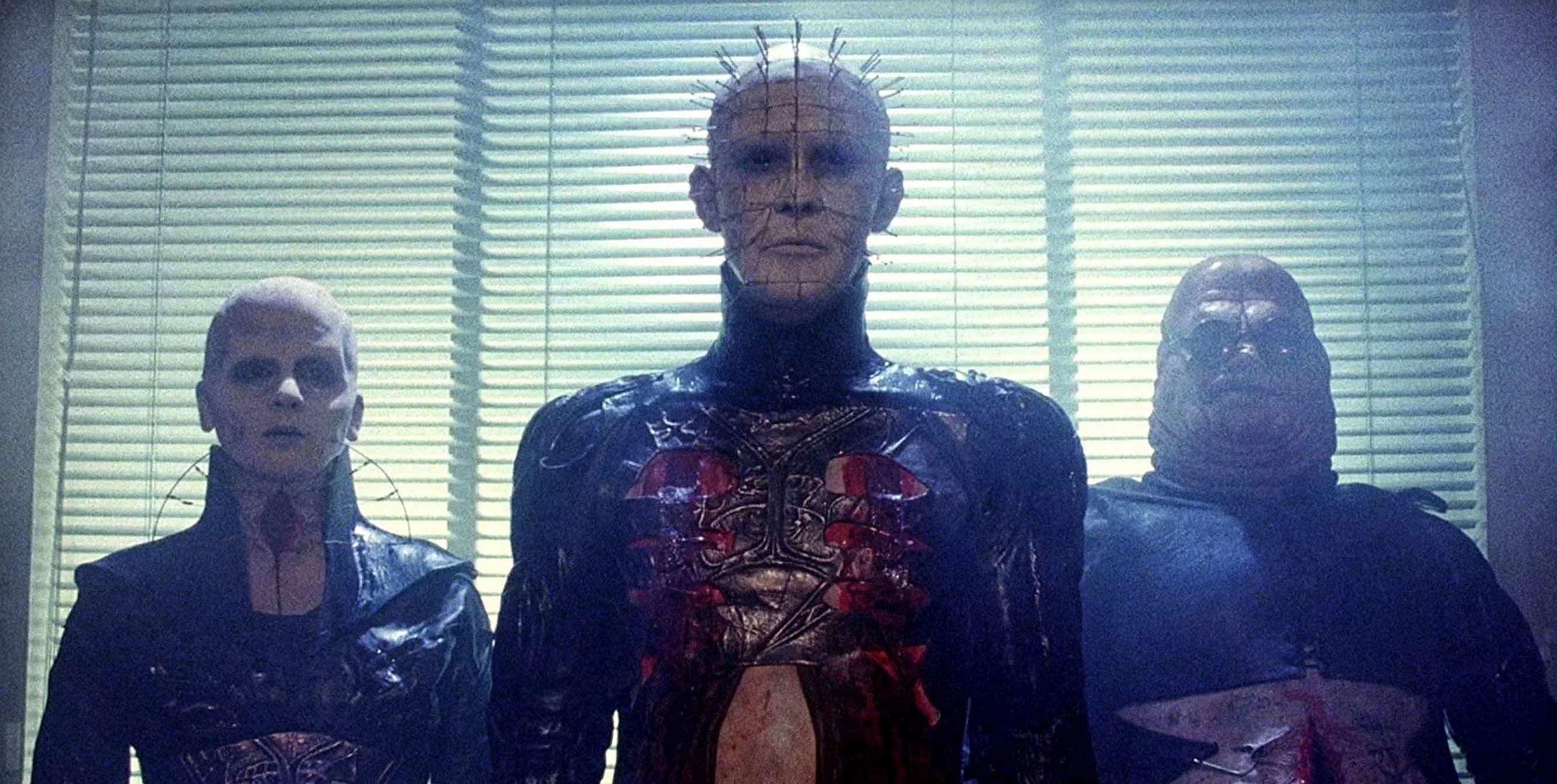

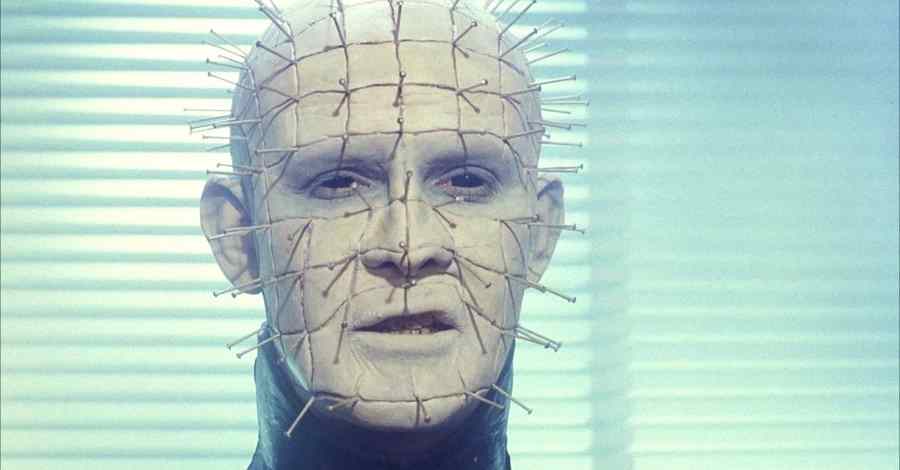

Then, just as Freddy began to dilute himself after the release of Dream Warriors, when he became a pop culture icon and therefore no longer a boogeyman, there came Pinhead. Whereas Freddy was front and center by that point, Pinhead was a monster who barely appeared in his own movie. He’s in Hellraiser for just over six minutes and yet in that time he resonated with audiences around the world. Part of that is due to the incredible visual design, of course, while the rest comes down to Doug Bradley and the sparse but incredible lines of dialogue that Barker wrote for him.

He was not a major part of the film, but he was what people clearly wanted, so it was Pinhead’s face on the posters. It was Pinhead on the VHS and DVD’s. His influences harken back to Mephistopheles in all incarnations of Faust—particularly Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus—as well as Dracula, specifically Christopher Lee’s portrayal in the Hammer films. Pinhead is one of the very few eloquent modern monsters. It’s hard to name many other contemporaries that spawned their own franchises and yet had a sense of class. The only one that really comes close is the Candyman, another Barker creation.

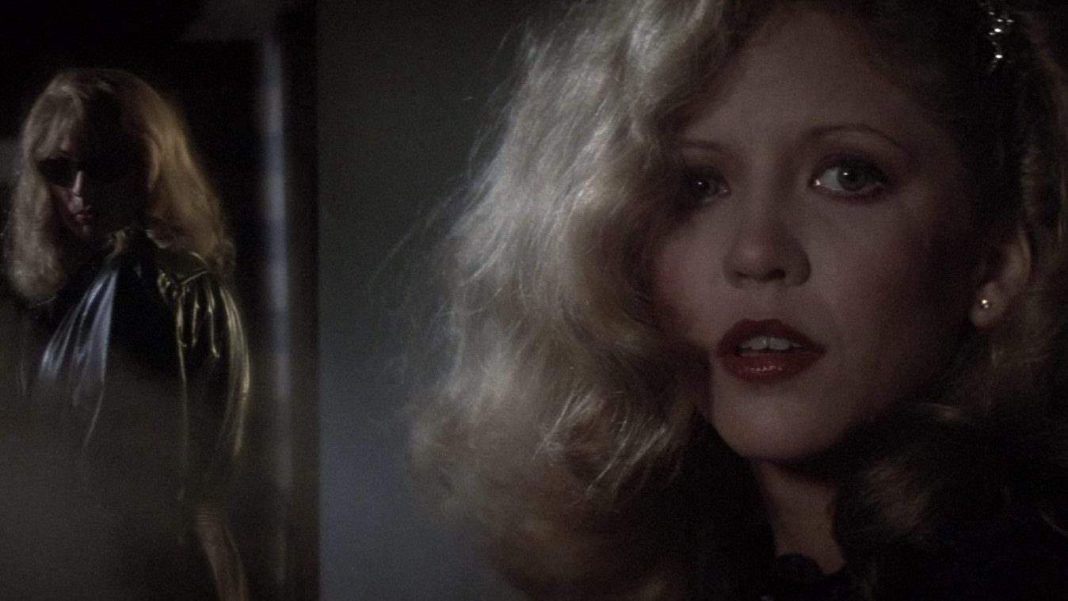

It took virtually no time at all for Pinhead to become an icon. They knew by the end of filming the original that there would be a sequel, and the sequel generated a ton of positive buzz. With good reason, too, as it’s one of the best sequels ever made to a horror picture. It was even clear to the filmmakers that people wanted to see more of Pinhead going into the second feature, despite the fact that Hellbound: Hellraiser II was completed and released less than a year after the original. Audiences latched onto this monster. While the lead Cenobite does not have much more screen time in the second than he does in the first the new scenes are crucial. We see glimpses of his backstory, of the man he used to be before his own broken spirit led him to uncover the box.

It took virtually no time at all for Pinhead to become an icon. They knew by the end of filming the original that there would be a sequel, and the sequel generated a ton of positive buzz. With good reason, too, as it’s one of the best sequels ever made to a horror picture. It was even clear to the filmmakers that people wanted to see more of Pinhead going into the second feature, despite the fact that Hellbound: Hellraiser II was completed and released less than a year after the original. Audiences latched onto this monster. While the lead Cenobite does not have much more screen time in the second than he does in the first the new scenes are crucial. We see glimpses of his backstory, of the man he used to be before his own broken spirit led him to uncover the box.

Pinhead has always resonated with people because he is a highly intelligent monster. Like the best villains, he would never use that word to describe himself. The Scarlet Gospels delivers him to an inevitable character point, one where the traces can be seen right back to the beginning: He is a representation of order, a patchwork of precision and a High Priest devoted to his faith, but one who longs to be an anarchist. Even though we never saw too much of what led Elliot Spencer to find the box and become the creature he became, it’s not hard to imagine that his journey in The Scarlet Gospels rivals his original journey to seek out the Lament Configuration in the first place.

He is one of the biggest, most recognizable horror icons on the planet. He has earned his death. He deserves his death. And yet he will be missed. With all of the pain he’s inflicted on the page and screen, all the horrible things he has done, we’re allowed to take pleasure in his death. There’s a sense of satisfaction to it, but at the same time there’s a sense of loss. Even the people who are glad to see him go may feel a tinge of pain, believing that he’s gone too soon. Ultimately, what could be more Hellraiser than that?