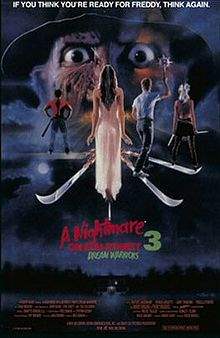

Wes Craven wrote and directed the original A Nightmare on Elm Street in 1984, introducing the world to dream killer Freddy Krueger and ultimate Final Girl Nancy Thompson. Craven had never intended it to spawn a franchise, and chose not to return for the first sequel the following year. When offered the chance to take on the third film in 1987, however, he agreed.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors marks the return of Nancy Thompson to the series, who has become a psychologist and dream expert since we last saw her, and is the new hire at a mental hospital which is housing a number of troubled teens. These teens are all being hunted in their sleep by Krueger, and Nancy teaches them to harness the power of their dreams to defeat him. Dream Warriors is, for many fans, their favorite entry in the franchise. However, it was hardly the story that Craven wanted to tell.

Wes Craven’s original script, written with Bruce Wagner, was heavily rewritten by Frank Darabont and Chuck Russell to the point where most of the similarities are superficial at best. When viewed in light of all the entries that came after, Craven’s vision gives us an alternate-universe view of what could have been, and where the franchise might have gone.

Wes Craven’s original script, written with Bruce Wagner, was heavily rewritten by Frank Darabont and Chuck Russell to the point where most of the similarities are superficial at best. When viewed in light of all the entries that came after, Craven’s vision gives us an alternate-universe view of what could have been, and where the franchise might have gone.

In this alternate take, Nancy is not any sort of a dream expert and has spent the last several years crossing the country in search of her missing father, who has embarked on a solo mission to find a way to destroy Freddy Krueger. She does, however, still wind up employed at the mental hospital after wrecking her car in a small town and befriending one of the locals, psychiatrist Neil Guiness (Neil Gordon in the film), who hires her as his assistant. She is introduced to Neil’s patients, a group of troubled teenagers who may share the names of the characters that we are familiar with, but are in some cases markedly different.

Taryn, for instance, is not a drug-addicted punk rocker but rather an implied pyromaniac. Joey is not an able-bodied mute but “frail and spasmodic”, and he speaks (infrequently) in confused and nonsensical verse. Philip is still a sleepwalker, but he is not a puppet maker. In this version, the puppet maker is Laredo, a character that does not exist in the film, who also contains elements of the yet-to-be-written Will. Kincaid, Jennifer, and Kirsten are mostly unchanged.

Though these “Dream Warriors” do figure heavily into the climax, aside from Kirsten, they are not nearly as integral to the rest of the plot as they are in the film. Here, Nancy learns of another patient kept isolated in a different wing of the hospital—a man diagnosed as schizophrenic after having plucked out his eyes and attempting to burn down an abandoned house. As it turns out, this patient is Nancy’s missing father, and the house he tried to burn down was the house that Krueger was born in. Sending it to ashes, he says, is the only way to truly destroy Freddy.

Though these “Dream Warriors” do figure heavily into the climax, aside from Kirsten, they are not nearly as integral to the rest of the plot as they are in the film. Here, Nancy learns of another patient kept isolated in a different wing of the hospital—a man diagnosed as schizophrenic after having plucked out his eyes and attempting to burn down an abandoned house. As it turns out, this patient is Nancy’s missing father, and the house he tried to burn down was the house that Krueger was born in. Sending it to ashes, he says, is the only way to truly destroy Freddy.

Destroying the house becomes the central theme of the story (punctuated with the occasional nightmare death, of course), though it’s not as simple as you would think. Attempts to burn it down in the real world prove ineffective, as if it’s somehow protected. Instead, the fire has to originate in the dream world, a mission that Nancy leads the surviving teenagers on, utilizing Kirsten’s ability to pull others into—and out of—dreams at will. But once the fire is set, and Kirsten pulls everyone out of the dream, Freddy has tagged along for the ride, and all boundaries between the waking world and the dream world seem to dissolve.

There’s a manic chase scene in which Kirsten effectively teleports everyone from one location to another with Freddy in hot pursuit—a power that serves to make her less of a dream warrior and more of an X-Man. In the end, with only Kirsten and Neil as survivors, the house is somehow “reborn” through the flames, and Kirsten finds herself in the home on the day that Freddy was born. After discovering the body of his mother in bed, having died in childbirth, Kirsten takes the newborn baby and bashes it against the wall repeatedly, before finally stabbing it to death (!) with Freddy’s own glove. She then wakes up outside the house, which has finally been burned down, the nightmare presumably at an end.

There’s a manic chase scene in which Kirsten effectively teleports everyone from one location to another with Freddy in hot pursuit—a power that serves to make her less of a dream warrior and more of an X-Man. In the end, with only Kirsten and Neil as survivors, the house is somehow “reborn” through the flames, and Kirsten finds herself in the home on the day that Freddy was born. After discovering the body of his mother in bed, having died in childbirth, Kirsten takes the newborn baby and bashes it against the wall repeatedly, before finally stabbing it to death (!) with Freddy’s own glove. She then wakes up outside the house, which has finally been burned down, the nightmare presumably at an end.

In the wrap-up, we learn that Nancy, though dead, visits Neil in his sleep every night. And just before the closing credits roll, the camera pans to a paper mâché model of the old Krueger house crafted by Joey, which Neil has kept as a memento…and inside one of the windows, a light turns on.

Perhaps the nightmare isn’t over after all.

The script, if nothing else, is certainly an interesting read. Freddy is much more vulgar here than he ever appears onscreen, casually dropping the dreaded C-word in reference to the females, and using homosexual epithets in reference to the males. At one point, he tells Kincaid that “your asshole belongs to me!”, and then proves his point by shoving his hand so far up the young man’s rectum that his glove emerges from Kincaid’s mouth. It’s apparent that Darabont and Russell wanted Freddy to be a killer that we loved, while Craven and Wagner wanted him to be a killer that we hated.

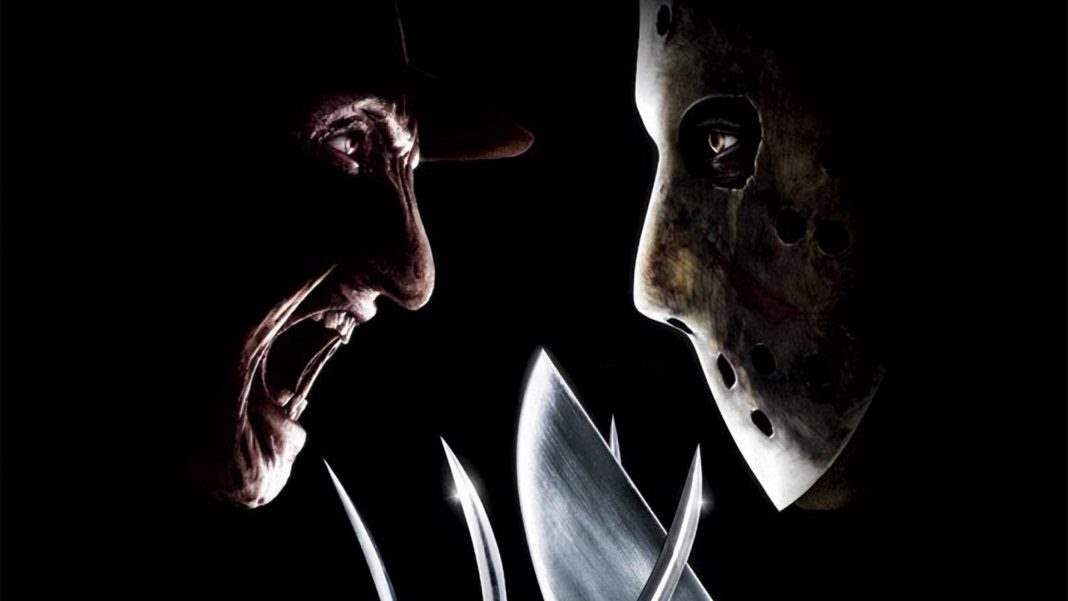

Wes Craven created these characters, and nothing can take that away from him. But with all due respect to the man, I have to say that I’m very glad we received the version of Dream Warriors that made it to the screen. Maybe it’s nostalgia talking, or just an inability to look past the continuity changes that this script would have brought to the franchise, but this sequel was such an important part of my youth, and so vital to me becoming the horror fan that I am, that I wouldn’t want it any other way.

Wes Craven created these characters, and nothing can take that away from him. But with all due respect to the man, I have to say that I’m very glad we received the version of Dream Warriors that made it to the screen. Maybe it’s nostalgia talking, or just an inability to look past the continuity changes that this script would have brought to the franchise, but this sequel was such an important part of my youth, and so vital to me becoming the horror fan that I am, that I wouldn’t want it any other way.